The Principles of Portfolio Management

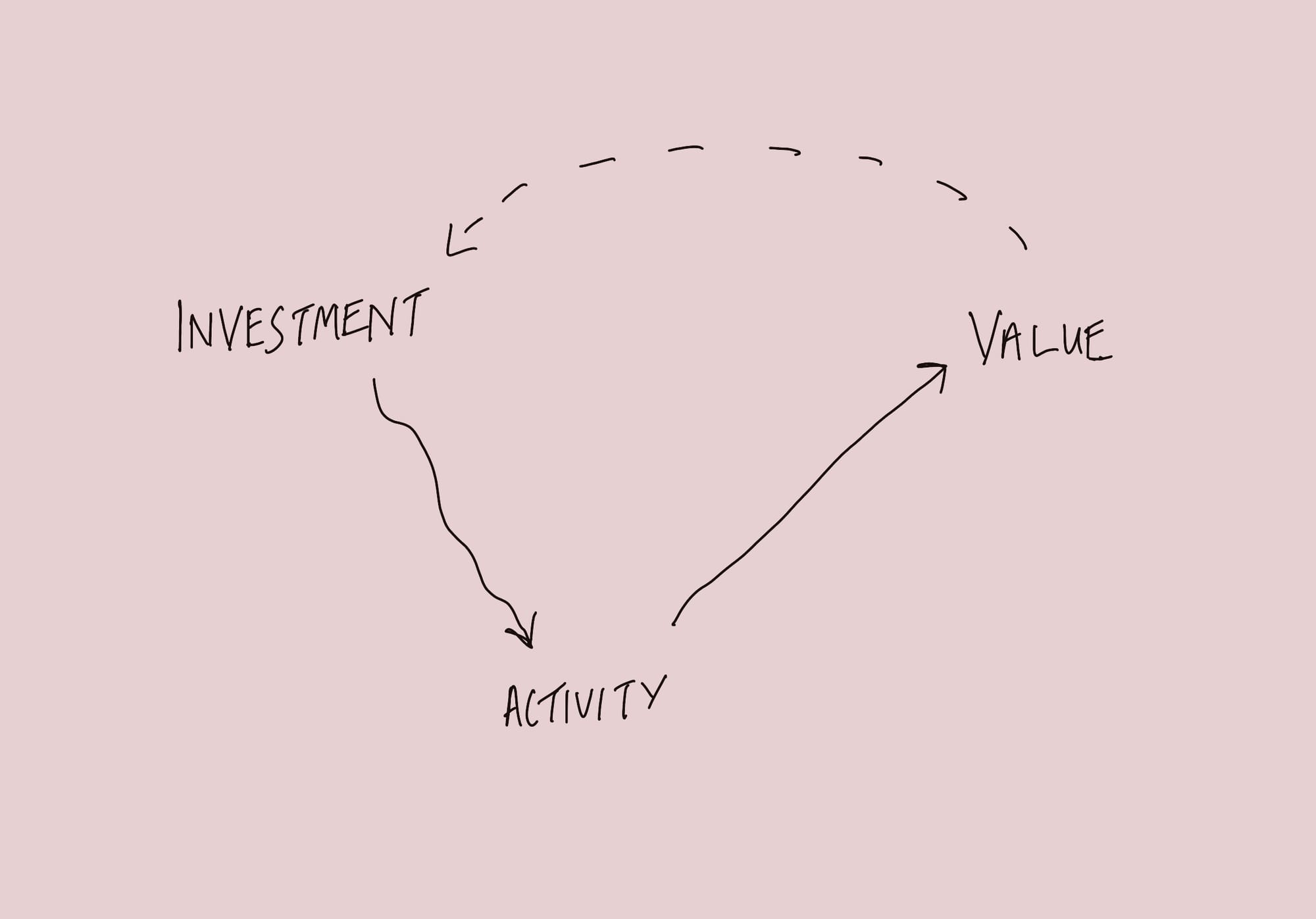

In this article I explain the principle of being able to see our investment, down to activity and back out to value - portfolio management

In many organisations (typically medium to large), there are often good people doing busy work that doesn't always lead to anything. There are also plenty of people doing work that is good and valuable but not connected directly to the strategic goals. It's good work that goes unrecognised and unmanaged. And of course, there are people coasting along and not adding much value to an organisation.

Besides all of the other stuff I talk about on this blog, one tactical approach I always recommend implementing is a portfolio management process.

A good portfolio management approach is essential in many organisations, large or small. In essence a portfolio management is a collection (and visibility) of all of the work going on under an umbrella of a portfolio.

It gives you:

- Visibility into how work is connected, how it flows and where it is stuck

- It connects work being done to value and investment

- It provides insights and data to teams, so they can improve

- It provides insights and data to managers and leaders, so they can make decisions - and re-allocate investment, people and resources.

- It provides a framework for running large projects in an effective way

It's highly likely your organisation may have several portfolios running in parallel (think rolling out a new IT system, launching a new customer platform, releasing a new product, rolling out Workday or something like that). These all need managing, tracking and deconstructing. And they all require investment, and there is some return on that investment, and there are people in the middle of this giving you their energy and attention.

As such, it's important that leaders and managers are investing in the right things, helping people add value - and then double checking the work that is happening is indeed adding value to the business.

As simple as this sounds, it's not common practice. At least in my experience.

Portfolios

Portfolio, the word, originates from "collecting together pieces of paper into some sort of system to be carried around". That definition, with a little bit of creativity is exactly what a portfolio in the workplace is; a collection of ideas, projects, work, actions and outcomes, brought together under a single view.

Many organisations don't have robust portfolio management in place. It's natural as work expands, new initiatives emerge and companies scale and grow. Without proper foresight it's natural for work to get out of control. It's natural for people to assume everyone will talk to each other, connect, share, align, collaborate, cooperate and come together to deliver value. Only it doesn't happen that way.

The system of work needs some control. And that's how a portfolio management system can help.

Now, I use the word "control" carefully here. Good portfolio management is not control of people, nor is it micromanagement, instead its visibility and understanding of the work being done, so that good decisions can be made about people, resources, priorities and of course, business effectiveness.

At Cultivated Management we never carry with us an absolute BEST structure or "way" for anything, instead we rely on principles and study.

Despite what many will say, there is no single best portfolio management approach, only one that is contextually useful to your organisation. If there was a single way, everyone would use it with success.

Instead, like with strategy, we rely on principles that allow us to approach the problem domain in a flexible way, whilst still ensuring we have the core elements needed to form a portfolio management.

There are lots of strong opinions about portfolio management, but opinionated people go around annoying other people with opinions. However, when you rely on principles, almost any approach could work. Without the principles though, it's highly likely many approaches won't work despite what the "sales people" tell you.

So, here are the principles we look for in a good portfolio management tool.

It should be possible to see, and trace, the investment being made, down to the activity happening to bring this to life, and then out to the value being created - in a single, simple way.

Depending on your work approach and methodology, and this is why context matters, you may have lots of hierarchies of work in play. These could be programmes, projects, initiatives, sprints etc. You could be running Kanban, agile(ish), MoreOrLessafe, waterfall, random - whatever approach works for you.

The principle remains the same - we should be able to connect the dots clearly and visibly from the investment, down to the activity and out to the value delivered.

We won't be touching on work structures or methodologies in this article, as it doesn't affect the core principles.

What I will say is that the more layers of work breakdown you have, the more complicated your work (managing, reporting, completing, connecting) will become. The tool you choose may also enforce a structure, so choose that carefully, or work within existing tools to simplify if you can.

I've worked in organisations that use 7 layers of work breakdown, all the way to a startup that used two. I prefer three 😄

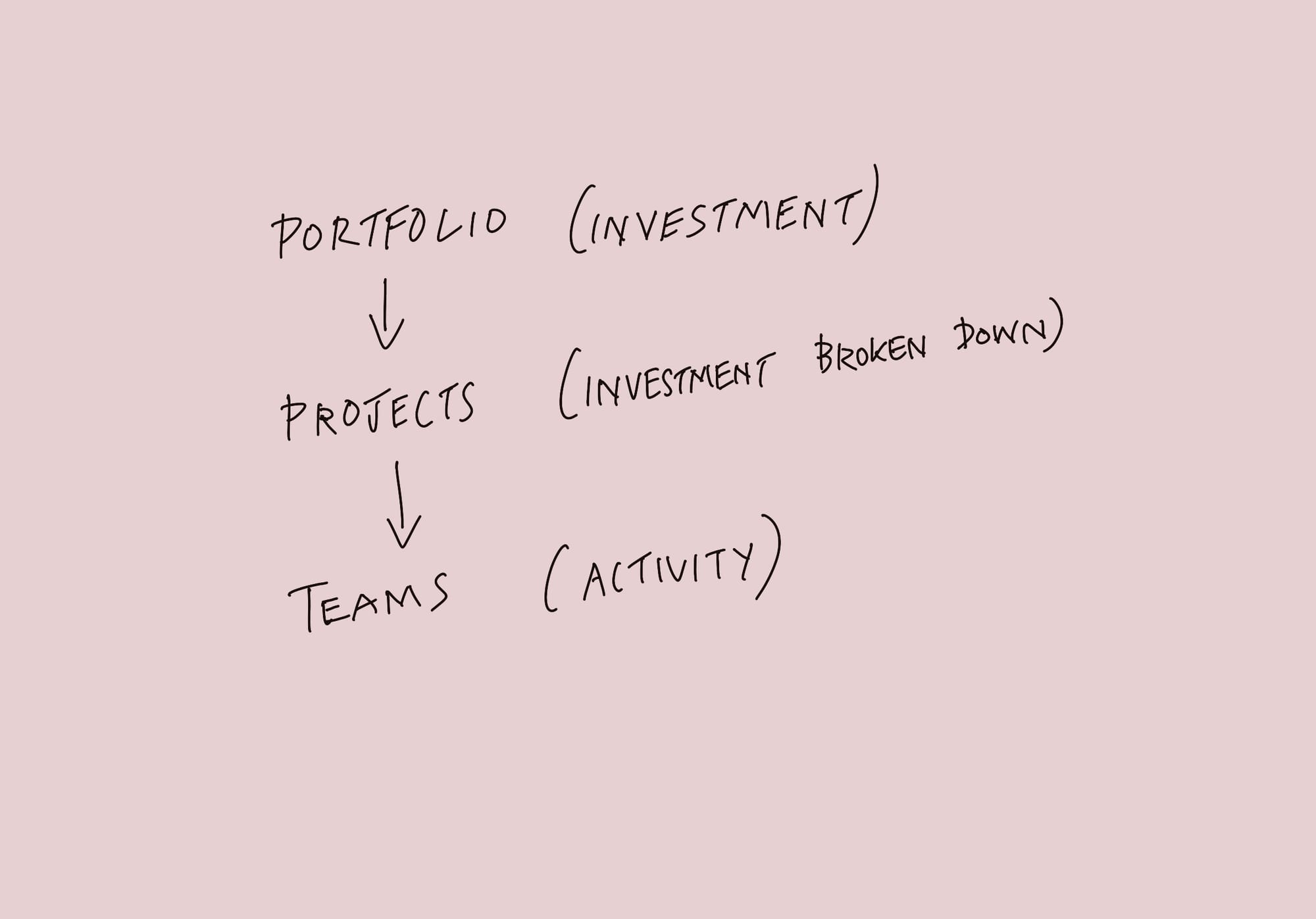

For the purposes of this article, let's keep it simple for explanation purposes and stick to three. Consider though that within levels 2 projects and level 3 teams, there could be multiple projects and teams.

- Portfolio [Investment]

- Projects (of which there could be many) [Investment broken down into projects]

- Teams (of which there could be many) [Activity]

For example, let's say we were rolling out a new Learning Management System. This is a portfolio of work, and in some organisations this could be a multi-million pound program of work.

Within this portfolio there will be programmes/projects of work, maybe related to installation/IT infrastructure, procurement, building learning content, rollout plan, training plan, communication plan, access and compliance etc.

Within these projects there will be teams (sometimes many teams) delivering this value.

Investment being made

The first part of the principle is that we need to clearly understand the investment being made.

When people are working in an organisation, they are using/spending the company's money to deliver something that is valuable. It's as simple as that. People cost money.

The executive and management team are using the company's money & resources to get something done - therefore it makes sense that what get's done is valuable.

This is a key aspect of a leadership and management role; to make sure people are working on the right things that add value.

That value may not be simply measured in financial outcomes - although everything ultimately comes back to keeping the business alive by either making more money, or not losing it through costs, loss of market share or waste.

- It could be about reputation, like fixing a broken software platform that customers are leaving in droves, or running a PR campaign to make amends for a mistake the company made.

- It could be environmental, like embarking on a program to make the products or services more efficient in terms of energy usage.

- It could be new platforms, services or features in software that customers need, and that sales people can sell.

- It could be fine tuning the operations of the business to reduce costs and increase effectiveness.

You get the idea. The company's leaders are allocating a portion of money (and sometimes this is a staggering amount) to get something of value done. That value will always, in some way come back to money, but money may not be the initial measure of value. (Hope that makes sense).

For example, maybe we're losing 100 customers a week and bringing in 50. This is likely not a good situation to be in. So, we may invest in a portfolio of work to improve the product or service. The value would likely be measured in the reduction of lost customers. This reduction of lost customers though, is ultimately a financial one.

We could argue that environmental and sustainability portfolios of work may not be directly financial. The cynical amongst us though will suggest these are related to marketing, PR and staff attraction........I'm not that cynical so these initiatives may not be tied to finances.

Anyway, you get the gist - we're investing money to get some form of value - and our assumption is the value we get is greater than the investment...... (with the notable exceptions of startup and R&D where money being spent is trying to find the market fit, get permission of the marketplace or find the next big thing. Ultimately though, we can't keep doing that forever....there needs to be some money at some point).

A good portfolio approach starts with understanding clearly what we're investing in.

- What problem are we trying to solve, or opportunity are we opening up?

- Why are we doing this - and what is the expected outcome in terms of value?

- Why is this portfolio of work worth doing? Why is it more important than other work we could get done?

- How will we know we are done and have been successful (i.e. how are we measuring success and progress)?

- What are our goals and outcomes?

- How does this tie to our strategy?

There are likely many more questions to ask.

We may not know all of the answers, so we may find we're investing some money to discover whether we should invest some more. This is a solid approach - and in this case, there is even more of a need for a portfolio approach that allows us to carefully measure and track everything that matters.

At the heart of these questions above is getting to the essence and value of why we're doing this work.

This is essential as we need to be sure we're not spending more than we're going to make (this happens A LOT!) and that we're not continuing to spend when we may have achieved our goals, or received the feedback we need to make a further decision.

Everything stems from absolute clarity around what we are investing in, how much we are investing and what we expect the valuable outcomes to be.

Activity being done

From this lofty set of outcomes and investment we will now focus people's energy and attention on delivering this value.

There is obviously a huge amount of communication, clarity, alignment and direction skipped here in this post but this article on strategy may help you if you're working on getting people mobilised around a clear direction.

With a good portfolio approach you should be able to see, track and trace all of the activity that is happening in service of the investment.

I've written many times before about how busy work is often being done and it has no connection with any investment, goal or strategy. It's also essential from an employee's perspective that they know how their work connects to the bigger picture. Without this we wonder why we're doing anything at all.

This is NOT about micromanagement, this is about insights, data and visibility so that decisions can be made about people, resource and even whether we should continue investing in the work.

If we have 1000 people all doing "something" but we have no idea what they're doing or how that ties back to the investment, we have a problem.

Of course, a good tool to track this would be helpful.

Portfolio tools come in many shapes and sizes, and are nothing more than containers with rules - so choose one that fits your context - and make EVERYONE use it.

Multiple tools cause problems with alignment, clarity and sometimes, you end up having to use some of the investment to pay people to plug the tools together just to see how you're tracking, and that makes no financial sense at all.

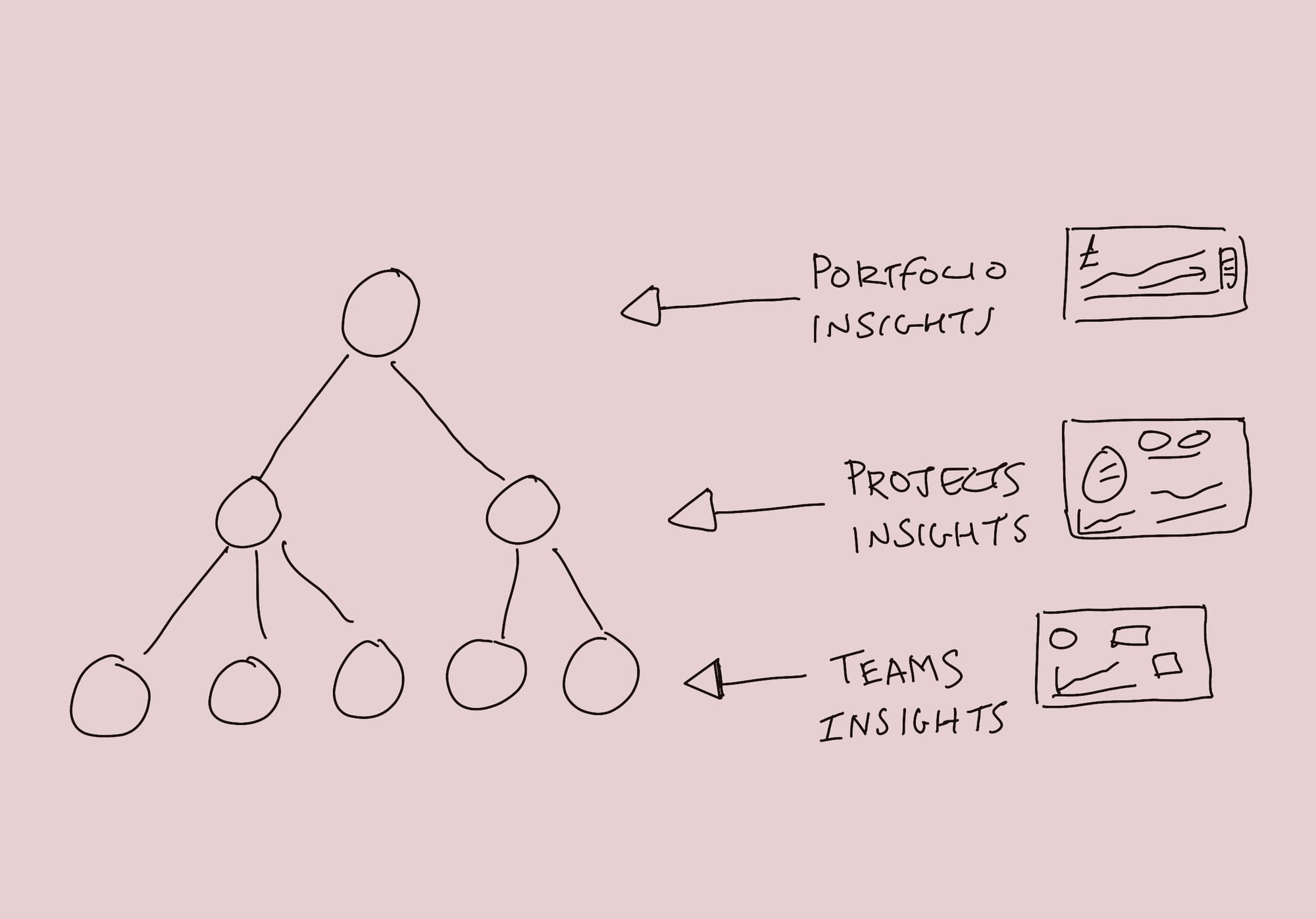

In my view, a good portfolio tool should give you at least three different lenses on the portfolio.

Here are the three basics I would expect to see from any tool.

- The day-to-day activity of the teams who are building the value (and in some organisation there could be hundreds of teams!).

- This view and data absolutely should belong to the team doing the work - don't let managers, project managers or leaders get too close to these numbers.

- These numbers, delivery charts, metrics and reports are for the team to work out how to improve and get smoother, quicker and faster. They are NOT for those higher up the org chart to use as a benchmark, comparison tool or stick to hit people with.

- Please keep these numbers away from leaders who wish to gamify them.

- I'd expect to see risks and dependencies that the team can own and overcome.

- The project status aggregated across all teams delivering on the project

- This view gives you a combined view with deliverables, roadmaps etc at a project level.

- This view should show how the overall project(s) are tracking in terms of deliverables against commitments.

- The numbers, metrics and measures here are aimed at project management, managers and leaders, who can use this data to inform prioritisation, stakeholder management and allocation of people, money and resources.

- With this view you should be able to see how a project (which is a collection of teams) is tracking.

- In our example of an LMS we could see how we're tracking on the IT infrastructure and content creation projects, which seem feasible to run in parallel.

- This should include project related risks and issues that require cross collaboration or interventions to address.

- I would expect some view of finances at this level also - i.e. how much have we spent so far etc

- Portfolio View

- At this level we're looking across the entire portfolio of projects (and teams).

- I'd expect to see risks, issues, progress against the overall goals and delivery status of those big ticket projects.

- This view is typically for senior leadership to understand how the business as a whole is tracking against the investment in this portfolio.

- I would also expect a financial view at this level - maybe in the same tool used to track progress, or, as I prefer, in a dedicated financial tracking too.

Each view is designed to give a relevant view for a specific audience.

If you've chosen your tool well (and I include a recommendation at the bottom of this article), then you should be able to drill up and down through all of these levels.

This is the test of the principle - using the tool (but remember, a tool is no substitution for communication).

Can you see the investment, down to activity and back out to value?

For example, if I am in a team, working on a task related to the content creation for the LMS, I should be able to jump up to the level above, and above and above (depending on your work item structure like stories, epics, initiatives etc) and eventually get all of the way to the Portfolio of LMS.

Equally, if I'm looking at the LMS portfolio at the highest level, I should be able to drill down through the hierarchy until I get to any single work item. I should be able to see the status of everything along the way.

A huge point here - everyone should be updating work through their tracking tool as they do it!

Again, I want to re-iterate that this is not micro management.

Using a work tracking tool at all levels in the organisation is essential for clarity and alignment. As an individual in a team, being able to see my work and manage it is key. What's next? What have I done? What am I working on? This is no different to having a running "to do" list in Todoist, or a bullet journal for our personal lives.

This is where many organisations fail. If people aren't used to writing down what they're doing, it can be a big mental and behavioural shift. But it's essential to ensure we're not duplicating work or missing key activity sets.

If we have zero visibility of work being done (that is directly linked to the value being created), then how can we possibly know how we're tracking, how to prioritise and when we are done?

Value being created

The next principal is the view of value.

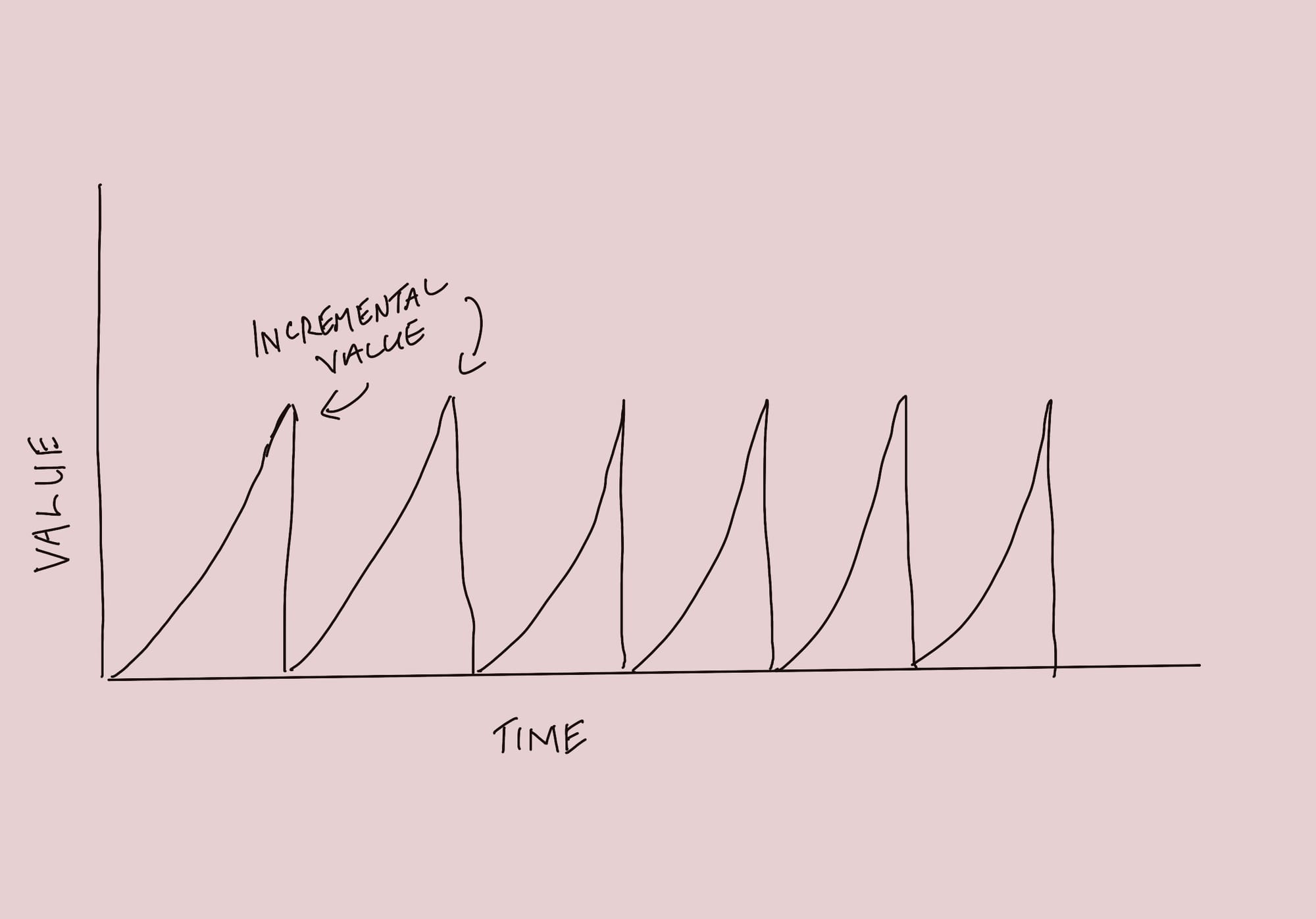

You may be working on a project that can be delivered in incremental steps of value, with each one aiming to release value that can be measured and delivered to your customers.

At each release of value you make money, or release the value. These could be new features in a software product that sales people can sell and people can buy.

We've just had a house rebuilt and it had incremental deliverables and payments in place. At each stage we had new bits of the house ready. Sure, we didn't get the full value until the whole house was built, but we could release funds for the build team - and see our house getting more complete as time went on. We could also pivot, critique, ask for better or change our plans at each stage.

Could you structure your delivery of value along the same lines?

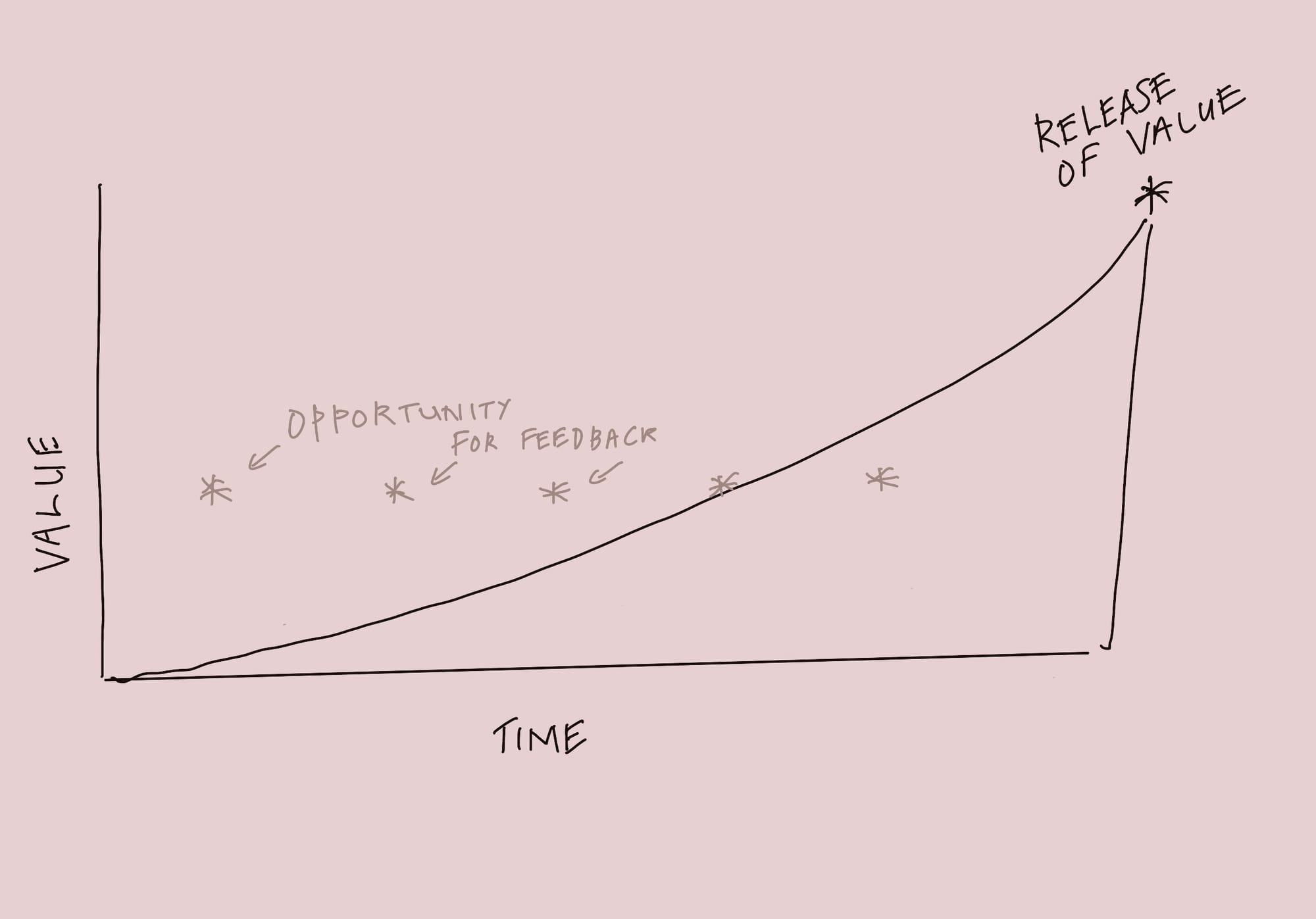

You may be working in a model where value is not released until everything is done, with no real option for incremental releases of value. A kind of all done or no value approach.

The downside to an "all done or no value" approach is that you may not find out you didn't deliver the value until the end (i.e. poor quality, wrong product, no market fit etc).

I always encourage an iterative feedback approach, even if the value is not realised until the end. That way you can keep checking you're doing the right work and be sure you're still investing in the right activities.

This is the context that only you will know, but at some point, whether incremental or not, you will need to understand the value being delivered.

You may be using any host of approaches within the delivery, such as waterfall, incremental, one of the many agile approach, quarterly planning yada yada yada. It kind of makes no difference to the principles we're using here, because at some point you must understand, see, measure and reflect on the value being delivered. The more often you can do this and get feedback, the better.

- Did you achieve the goals? Or are you currently achieving the goals?

- What do the measures, numbers and data tell us?

- Did we release the value?

- How much are we spending, or did spend, in terms of investment - and what was the return (remember, not all investments result in a financial outcome).

- Should you continue, pivot, short-cycle, stop?

Many many companies do not have a good, solid, reliable or simple way to measure the value being delivered. This all comes back to the first part of the principle - the investment. What are we investing, why and what do we expect in return. We can then test the value actually being released against what we expected. Sure, we may not know all of the details and our assumptions may be wrong - but that's why we test them along the way ideally.

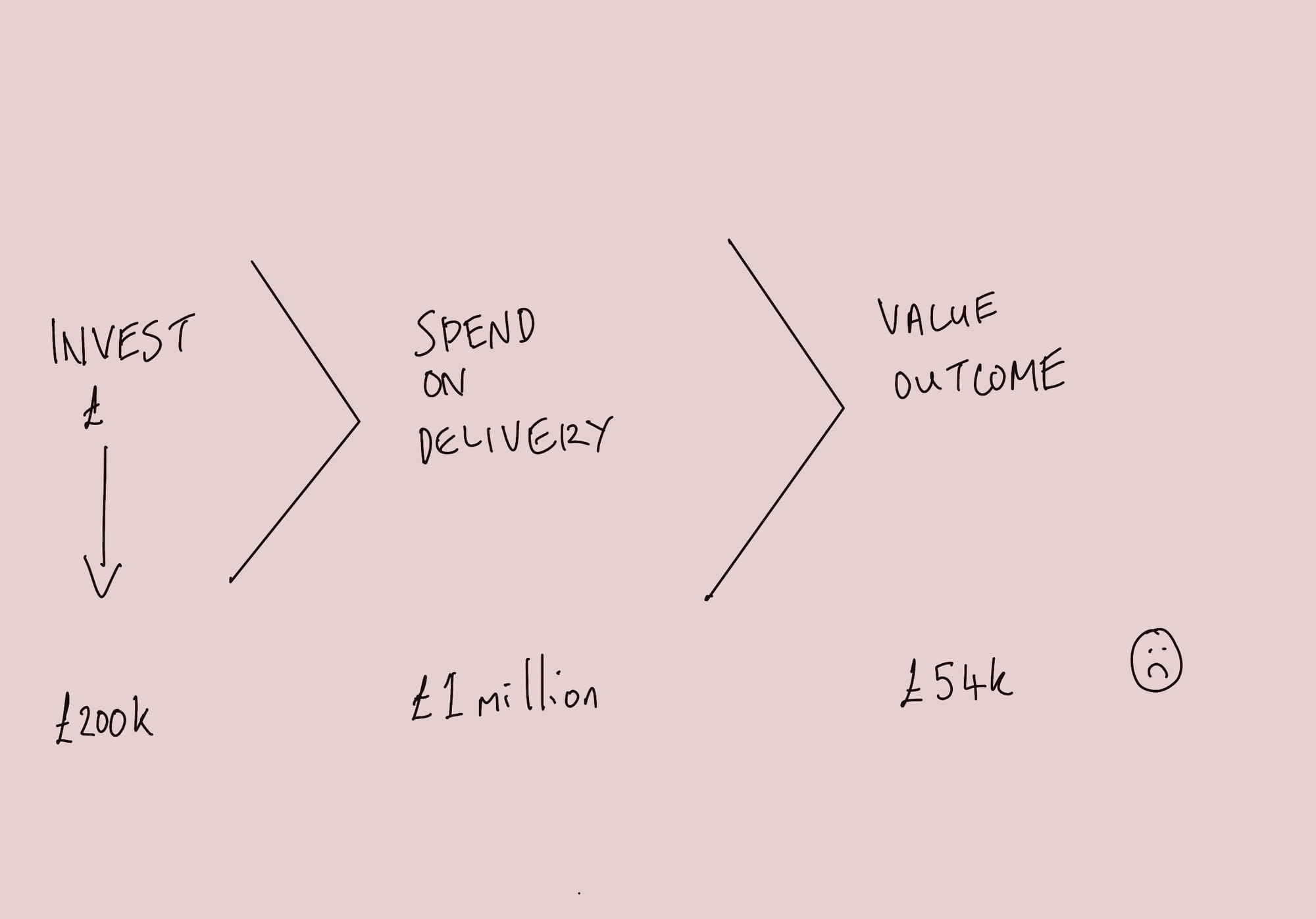

In one company they weren't tracking any work or finances other than in a large gantt chart updated monthly. They expected the cost of delivery to be £200k and the value released to be £400k.

They actually spent over £1 million on the delivery as they weren't tracking anything at all - so had no insights on whether to cancel, investigate problems, identify costs...etc

The £400k was an estimate they held during the investment work - in the end they only sold 200 licenses in the first year for this new software platform, equating to just £54k of revenue. And this didn't take into account any of the sales and marketing costs.

Their estimated value return on the investment was shady to start with but made even worse by the lack of tracking, clarity and rigour during delivery which meant they spent more than they expected without realising.

In one company they were spending a run rate of £700k per year on software engineers - this is how much it cost the business to run this team, irrelevant of whether these people did any work or not. And they didn't do much work for a year as the business couldn't work out what to invest in.

No goals, no outcomes just busy tech work tinkering with products......the engineers we're just doing "stuff" that someone had requested, with no obvious connection to any kind of specific investment or value return.

In one company they rolled out a new IT system with no obvious benefit or value associated to it - it cost them £4million......

In many companies people are busy building "stuff" and there's no obvious way to measure the success of this "stuff" and tie it back to an investment expectation.

Money, in business, is often thrown at projects, portfolios and initiatives based on "gut feel" or "it sounds plausible" with no obvious statement of return on the investment defined up front, usually with no real-time tracking or progress and then with no way to measure whether said "stuff" actually made any money or released value. There's also a whole host of problems that occur during delivery but I'll save that one for another day.

Portfolio management is NOT the answer to these problems - critical thinking, a good strategy and good leadership is. But, a decent portfolio process will highlight where things are missing, where you can pivot and change direction - and how your company are progressing towards goals.

For example, if you cannot tie the work being done to any investment, what's the problem? Is the investment not clear? Do you need a better tool? Is the work being done not valuable?

It goes without saying that a portfolio management process is only as good as the input, updates and outputs, but it should have the three elements present here:

- A clear indication of the investment and what the expected value is as an outcome (ideally with goals)

- The ability to see and connect ALL work associated with bringing this investment to life - all the way up and down within whatever work approach your company uses plus real time financials if possible on spend.

- The ability to measure and see the value delivered - and connect this back to the investment

Our personal money

Let's bring this to life by thinking about this in our personal lives. If someone came to you and asked for £100 to do some "work", you'd want to know what that work was, why it needed doing and what the value of it was.

- If they told you your £100 would give you £200 back, you'd likely ask some critical questions about how, why and by what means - and when.

- If they told you your £100 would save you £500 over a year on your energy bills, you'd want to see some numbers and evidence.

- If they told you it was for a good cause, you'd want to know what that cause was and what the £100 would be used for.

- Along the way with any of these, you'd probably want some way of measuring the investment to see how you're tracking, right?

Of course, some people don't apply much critical thinking and get robbed....but you get the point.

- If you have investments in the stock market, you're likely getting reports and updates on how that investment is tracking.

- If you have savings in the bank, your bank will be sending you statements so you can see how you're tracking.

If you have a job that needs doing, like some gardening for example, and you reached out to a gardener, you would expect a quote based on some clear deliverables and outcomes. You may even shop around for the best quote, or go with someone you trust and like.

You'd likely check every so often that the work was being done, or at least check it at the end to make sure it was what you asked for.

If the price goes up during the work due to a problem identified, you'd expect a clear explanation as to what the problem was, and a chance to negotiate depending on whether this project was worth it still. You use this visibility and insights to make decisions; spend more money, or live with the problem, or stop the work.

Yet, when we're in work we often abandon all of this critical thinking and insight, because it's not our money. It's the company's money. It's someone else's money. But the reality is - it is not somebody else's. It is your money (in a good company anyway). As the company makes money you should see the benefits - pay increase, better pension, health care, perks, a bit more job security, promotions, opportunity for growth etc.

So, we should be very careful with the company's money.

Yet many people are not and don't apply the same due diligence we would with our own money.

In some companies, people are spending money on gut feels, and hoping for the best. Leaders are investing in projects with no obvious return. Managers are not tracking outcomes and spend - and spending more than the value they get back. People are busy doing work that may have no actual value to the business.

But if we treated the company's money as our own - and used it to invest in work that had a return, and tracked it, and reconciled the value with the investment to make better decisions in the future, we'd need some way of doing this - and that is where a portfolio approach can help.

- What are we investing, how much, why and what are we expecting back from it?

- How are we tracking the activity? Are we wasting any effort, money, time etc? Are we stuck or blocked?

- How are we tracking the value? Did we release any yet? When are we releasing the value? Is this investment working? Was this a good investment? Can we short-cycle the investment? Or stop it before we lose even more?

We'd do this with our own money if we're sensible. Yet, we don't often do it with the company's money. Maybe it's time we did - and we may find we're a lot more critical about spending money, a lot more careful about tracking it and a lot more prudent when it comes to realising the value.

How you structure the technical and operational aspects of a portfolio management system, delivery methodology and tooling should be based on your context.

But at a principle level we should, at any given time, be able to see and trace our investment down to activity and back out to value. If we can't, what's our next step?